Art Installation of Life Size Plastic Alien Guy Not Fitting in

Conceptual art, also referred to as conceptualism, is art in which the concept(south) or thought(s) involved in the work take precedence over traditional artful, technical, and material concerns. Some works of conceptual art, sometimes called installations, may exist synthetic by anyone merely past following a set up of written instructions.[1] This method was fundamental to American artist Sol LeWitt's definition of conceptual fine art, one of the first to appear in print:

In conceptual fine art the thought or concept is the most of import aspect of the piece of work. When an creative person uses a conceptual form of art, information technology means that all of the planning and decisions are fabricated beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory matter. The idea becomes a auto that makes the art.[two]

Tony Godfrey, writer of Conceptual Fine art (Art & Ideas) (1998), asserts that conceptual art questions the nature of art,[3] a notion that Joseph Kosuth elevated to a definition of art itself in his seminal, early on manifesto of conceptual art, Fine art after Philosophy (1969). The notion that fine art should examine its ain nature was already a potent attribute of the influential art critic Clement Greenberg's vision of Mod art during the 1950s. With the emergence of an exclusively linguistic communication-based art in the 1960s, withal, conceptual artists such as Art & Language, Joseph Kosuth (who became the American editor of Fine art-Language), and Lawrence Weiner began a far more radical interrogation of art than was previously possible (meet beneath). One of the first and about of import things they questioned was the common assumption that the role of the artist was to create special kinds of material objects.[iv] [v] [6]

Through its association with the Young British Artists and the Turner Prize during the 1990s, in popular usage, peculiarly in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, "conceptual art" came to denote all contemporary fine art that does not practice the traditional skills of painting and sculpture.[7] Ane of the reasons why the term "conceptual art" has come up to be associated with diverse gimmicky practices far removed from its original aims and forms lies in the trouble of defining the term itself. As the artist Mel Bochner suggested equally early equally 1970, in explaining why he does not like the epithet "conceptual", information technology is not always entirely clear what "concept" refers to, and it runs the chance of being confused with "intention". Thus, in describing or defining a work of art every bit conceptual it is of import not to confuse what is referred to as "conceptual" with an creative person's "intention".

Precursors [edit]

The French creative person Marcel Duchamp paved the way for the conceptualists, providing them with examples of prototypically conceptual works — the readymades, for instance. The most famous of Duchamp'southward readymades was Fountain (1917), a standard urinal-basin signed by the artist with the pseudonym "R.Mutt", and submitted for inclusion in the almanac, united nations-juried exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York (which rejected it).[eight] The artistic tradition does not see a commonplace object (such as a urinal) equally art considering it is not made by an creative person or with any intention of being art, nor is it unique or hand-crafted. Duchamp'south relevance and theoretical importance for future "conceptualists" was later acknowledged by US artist Joseph Kosuth in his 1969 essay, Art after Philosophy, when he wrote: "All fine art (after Duchamp) is conceptual (in nature) because art but exists conceptually".

In 1956 the founder of Lettrism, Isidore Isou, developed the notion of a work of art which, by its very nature, could never be created in reality, merely which could nevertheless provide aesthetic rewards by being contemplated intellectually. This concept, also called Art esthapériste (or "infinite-aesthetics"), derived from the infinitesimals of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz – quantities which could not actually exist except conceptually. The electric current incarnation (Equally of 2013[update]) of the Isouian movement, Excoördism, self-defines equally the art of the infinitely large and the infinitely modest.

Origins [edit]

In 1961, philosopher and artist Henry Flynt coined the term "concept art" in an commodity bearing the same name which appeared in the proto-Fluxus publication An Anthology of Chance Operations.[9] Flynt'southward concept art, he maintained, devolved from his notion of "cognitive nihilism", in which paradoxes in logic are shown to evacuate concepts of substance. Drawing on the syntax of logic and mathematics, concept art was meant jointly to supersede mathematics and the formalistic music then current in serious art music circles.[10] Therefore, Flynt maintained, to merit the label concept fine art, a work had to exist a critique of logic or mathematics in which a linguistic concept was the material, a quality which is absent-minded from subsequent "conceptual fine art".[xi]

The term assumed a different meaning when employed by Joseph Kosuth and by the English Art and Language grouping, who discarded the conventional art object in favour of a documented critical enquiry, that began in Fine art-Language: The Periodical of Conceptual Art in 1969, into the artist's social, philosophical, and psychological status. By the mid-1970s they had produced publications, indices, performances, texts and paintings to this end. In 1970 Conceptual Art and Conceptual Aspects, the offset defended conceptual-art exhibition, took place at the New York Cultural Center.[12]

The critique of formalism and of the commodification of art [edit]

Conceptual art emerged every bit a move during the 1960s – in part as a reaction confronting formalism equally then articulated by the influential New York art critic Clement Greenberg. According to Greenberg Modern art followed a process of progressive reduction and refinement toward the goal of defining the essential, formal nature of each medium. Those elements that ran counter to this nature were to exist reduced. The job of painting, for example, was to ascertain precisely what kind of object a painting truly is: what makes it a painting and nothing else. As it is of the nature of paintings to be apartment objects with sail surfaces onto which colored paint is practical, such things as figuration, iii-D perspective illusion and references to external field of study matter were all found to be extraneous to the essence of painting, and ought to be removed.[13]

Some have argued that conceptual art continued this "dematerialization" of art by removing the need for objects altogether,[14] while others, including many of the artists themselves, saw conceptual art as a radical suspension with Greenberg's kind of formalist Modernism. Later artists connected to share a preference for fine art to be self-critical, besides every bit a distaste for illusion. However, by the end of the 1960s it was certainly clear that Greenberg's stipulations for fine art to continue within the confines of each medium and to exclude external subject thing no longer held traction.[15] Conceptual art also reacted confronting the commodification of art; it attempted a subversion of the gallery or museum as the location and determiner of fine art, and the art market equally the possessor and benefactor of art. Lawrence Weiner said: "Once you know about a work of mine you ain it. There'south no manner I can climb inside somebody's head and remove information technology." Many conceptual artists' work can therefore merely be known about through documentation which is manifested by it, e.m., photographs, written texts or displayed objects, which some might contend are not in and of themselves the art. It is sometimes (as in the work of Robert Barry, Yoko Ono, and Weiner himself) reduced to a set of written instructions describing a work, but stopping short of actually making information technology—emphasising the thought every bit more than important than the artifact. This reveals an explicit preference for the "art" side of the ostensible dichotomy between art and craft, where art, unlike craft, takes identify within and engages historical soapbox: for example, Ono's "written instructions" make more sense aslope other conceptual art of the time.

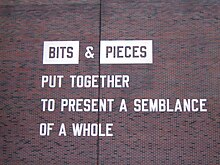

Lawrence Weiner. Bits & Pieces Put Together to Present a Semblance of a Whole, The Walker Fine art Heart, Minneapolis, 2005.

Linguistic communication and/equally art [edit]

Language was a fundamental concern for the starting time moving ridge of conceptual artists of the 1960s and early 1970s. Although the utilisation of text in fine art was in no way novel, but in the 1960s did the artists Lawrence Weiner, Edward Ruscha,[16] Joseph Kosuth, Robert Barry, and Art & Linguistic communication brainstorm to produce fine art by exclusively linguistic means. Where previously linguistic communication was presented as 1 kind of visual element alongside others, and subordinate to an overarching composition (due east.g. Synthetic Cubism), the conceptual artists used language in place of castor and canvas, and allowed it to signify in its ain right.[17] Of Lawrence Weiner'south works Anne Rorimer writes, "The thematic content of private works derives solely from the import of the linguistic communication employed, while presentational means and contextual placement play crucial, nonetheless dissever, roles."[18]

The British philosopher and theorist of conceptual fine art Peter Osborne suggests that among the many factors that influenced the gravitation toward language-based art, a central role for conceptualism came from the turn to linguistic theories of meaning in both Anglo-American analytic philosophy, and structuralist and post structuralist Continental philosophy during the heart of the twentieth century. This linguistic turn "reinforced and legitimized" the management the conceptual artists took.[xix] Osborne as well notes that the early conceptualists were the first generation of artists to complete caste-based university training in art.[20] Osborne later made the observation that contemporary art is postal service-conceptual [21] in a public lecture delivered at the Fondazione Antonio Ratti, Villa Sucota in Como on July 9, 2010. Information technology is a claim made at the level of the ontology of the piece of work of fine art (rather than say at the descriptive level of way or movement).

The American art historian Edward A. Shanken points to the case of Roy Ascott who "powerfully demonstrates the significant intersections betwixt conceptual art and art-and-technology, exploding the conventional autonomy of these art-historical categories." Ascott, the British creative person nearly closely associated with cybernetic fine art in England, was not included in Cybernetic Serendipity because his utilise of cybernetics was primarily conceptual and did not explicitly utilise technology. Conversely, although his essay on the application of cybernetics to fine art and art pedagogy, "The Construction of Modify" (1964), was quoted on the dedication page (to Sol LeWitt) of Lucy R. Lippard's seminal Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Fine art Object from 1966 to 1972, Ascott'south anticipation of and contribution to the formation of conceptual fine art in Britain has received scant recognition, perhaps (and ironically) considering his piece of work was also closely allied with art-and-technology. Another vital intersection was explored in Ascott'south use of the thesaurus in 1963 telematic connections:: timeline, which drew an explicit parallel between the taxonomic qualities of verbal and visual languages – a concept would be taken up in Joseph Kosuth's Second Investigation, Proposition 1 (1968) and Mel Ramsden's Elements of an Incomplete Map (1968).

Conceptual fine art and artistic skill [edit]

By adopting language equally their exclusive medium, Weiner, Barry, Wilson, Kosuth and Art & Language were able to sweep bated the vestiges of authorial presence manifested past formal invention and the handling of materials.[eighteen]

An of import difference betwixt conceptual fine art and more "traditional" forms of art-making goes to the question of artistic skill. Although skill in the treatment of traditional media often plays little part in conceptual art, information technology is difficult to argue that no skill is required to brand conceptual works, or that skill is ever absent from them. John Baldessari, for example, has presented realist pictures that he commissioned professional sign-writers to pigment; and many conceptual performance artists (eastward.grand. Stelarc, Marina Abramović) are technically accomplished performers and skilled manipulators of their own bodies. It is thus non and then much an absence of skill or hostility toward tradition that defines conceptual fine art every bit an evident condone for conventional, modern notions of authorial presence and of individual creative expression.[ citation needed ]

Contemporary influence [edit]

Proto-conceptualism has roots in the rise of Modernism with, for example, Manet (1832–1883) and later Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). The first moving ridge of the "conceptual fine art" movement extended from approximately 1967[22] to 1978. Early on "concept" artists like Henry Flynt (1940– ), Robert Morris (1931–2018), and Ray Johnson (1927–1995) influenced the later, widely accepted move of conceptual fine art. Conceptual artists similar Dan Graham, Hans Haacke, and Lawrence Weiner have proven very influential on subsequent artists, and well-known contemporary artists such as Mike Kelley or Tracey Emin are sometimes labeled[ by whom? ] "second- or third-generation" conceptualists, or "mail-conceptual" artists (the prefix Post- in art tin frequently be interpreted as "because of").

Contemporary artists have taken up many of the concerns of the conceptual art movement, while they may or may non term themselves "conceptual artists". Ideas such equally anti-commodification, social and/or political critique, and ideas/information as medium go along to be aspects of contemporary art, particularly amidst artists working with installation art, functioning fine art, net.fine art and electronic/digital art.[23] [ need quotation to verify ]

Notable examples [edit]

- 1913 : Wheel Wheel (Roue de bicyclette) by Marcel Duchamp. Assisted readymade. Bicycle wheel mounted by its fork on a painted wooden stool. The first readymade, fifty-fifty though he did not have the idea for readymades until two years afterwards. The original was lost. Also, recognized every bit the first kinetic sculpture.[24]

- 1914 : Pharmacy (Pharmacie) by Marcel Duchamp. Rectified readymade. Gouache on chromolithograph of a scene with bare trees and a winding stream to which he added two circles, ruby and green.

- 1914 : Bottle Rack (also called Bottle Dryer or Hedgehog) (Egouttoir or Porte-bouteilles or Hérisson) by Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. A galvanized iron bottle drying rack that Duchamp bought every bit an "already fabricated" sculpture, but it gathered grit in the corner of his Paris studio. Two years later in 1916, in correspondence from New York with his sis, Suzanne Duchamp in France, he expresses a desire to make information technology a readymade. Suzanne, looking after his Paris studio, has already disposed of it.

- 1915 : In Advance of the Broken Arm (En prévision du bras cassé) by Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. Snow shovel on which Duchamp carefully painted its title. The offset piece the artist officially chosen a "readymade".

- 1915 : Pulled at four pins past Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. An unpainted chimney ventilator that turns in the wind. Duchamp liked that the literal translation meant null in English and had no relation to the object.

- 1916 : With Hidden Racket (A bruit secret) by Marcel Duchamp. Assisted readymade. A ball of twine between two brass plates, joined past four screws. An unknown object has been placed in the ball of twine past Duchamp's friend, Walter Arensberg.

- 1916 : Comb (Peigne) by Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. Steel domestic dog training comb inscribed along the border.

- 1917 : Traveller'southward Folding Item (...pliant,... de voyage) by Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. Underwood Typewriter cover.

- 1916–17 : Apolinère Enameled, 1916–1917. Rectified readymade. An altered Sapolin pigment advertising.

- 1917 : Fountain by Marcel Duchamp, described in an article in The Contained as the invention of conceptual art. It is likewise an early example of an Institutional Critique[25]

- 1917 : 'Trap (Trébuchet) by Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. Wood and metal coatrack attached to floor.

- 1917 : Hat Rack (Porte-chapeaux), c. 1917, past Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. A wooden hatrack.[26]

- 1919 : 50.H.O.O.Q. by Marcel Duchamp. Rectified readymade. Pencil on a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa on which he drew a goatee and moustache titled with a coarse pun.[27]

- 1919 : Unhappy readymade, by Marcel Duchamp. Assisted readymade. Duchamp instructed his sister Suzanne to hang a geometry textbook from the balustrade of her Paris flat. Suzanne carried out the instructions and painted a picture of the result.

- 1919 : 50 cc of Paris Air (50 cc air de Paris, Paris Air or Air de Paris) past Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. A drinking glass ampoule containing air from Paris. Duchamp took the ampoule to New York City in 1920 and gave information technology to Walter Arensberg as a souvenir.

- 1920 : Fresh Widow by Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. An altered French window creating a pun.

- 1921 : Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? by Marcel Duchamp. Assisted readymade. Marble cubes in the shape of sugar lumps with a thermometer and cuttle basic in a minor bird cage.

- 1921 : Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette by Marcel Duchamp. Assisted readymade. An altered perfume bottle in the original box.[28]

- 1921 : The Brawl at Austerlitz by Marcel Duchamp. Readymade. Like Fresh Widow, made by a carpenter co-ordinate to Duchamp's specifications.

- 1923 : Wanted, $2,000 Advantage by Marcel Duchamp. Rectified readymade. Photographic collage on poster.

- 1952 : The premiere of American experimental composer John Cage's work, 4′33″, a three-motion composition, performed by pianist David Tudor on August 29, 1952, in Bohemian Concert Hall, Woodstock, New York, as office of a recital of contemporary piano music.[29] It is unremarkably perceived every bit "four minutes thirty-three seconds of silence".

- 1953 : Robert Rauschenberg produces Erased De Kooning Drawing, a cartoon past Willem de Kooning which Rauschenberg erased. It raised many questions almost the central nature of art, challenging the viewer to consider whether erasing another artist'due south piece of work could be a creative act, too as whether the piece of work was only "art" because the famous Rauschenberg had done it.

- 1955 : Rhea Sue Sanders creates her outset text pieces of the serial pièces de complices, combining visual art with poetry and philosophy, and introducing the concept of complicity: the viewer must achieve the art in her/his imagination.[xxx]

- 1956 : Isidore Isou introduces the concept of infinitesimal art in Introduction à une esthétique imaginaire (Introduction to Imaginary Aesthetics).

- 1957: Yves Klein, Aerostatic Sculpture (Paris), composed of 1001 blue balloons released into the sky from Galerie Iris Clert to promote his Proposition Monochrome; Blue Epoch exhibition. Klein as well exhibited 1 Minute Fire Painting, which was a blue panel into which 16 firecrackers were prepare. For his next major exhibition, The Void in 1958, Klein alleged that his paintings were now invisible – and to testify information technology he exhibited an empty room.

- 1958: George Brecht invents the Event Score [31] which would become a key feature of Fluxus. Brecht, Dick Higgins, Allan Kaprow, Al Hansen, Jackson MacLow and others studied with John Cage between 1958 and 1959 at the New Schoolhouse leading directly to the creation of Happenings, Fluxus and Henry Flynt's concept fine art. Event Scores are elementary instructions to complete everyday tasks which can be performed publicly, privately, or not at all.

- 1958: Wolf Vostell Das Theater ist auf der Straße/The theater is on the street. The first Happening in Europe.[32]

- 1960: Yves Klein'south action chosen A Leap Into The Void, in which he attempts to fly past leaping out of a window. He stated: "The painter has simply to create i masterpiece, himself, constantly."

- 1960: The artist Stanley Brouwn declares that all the shoe shops in Amsterdam plant an exhibition of his work.

- 1961: Wolf Vostell Cityrama, in Cologne – the kickoff Happening in Germany.

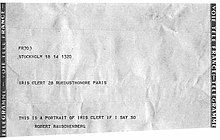

- 1961: Robert Rauschenberg sent a telegram to the Galerie Iris Clert which read: 'This is a portrait of Iris Clert if I say so.' as his contribution to an exhibition of portraits.

- 1961: Piero Manzoni exhibited Artist'southward Shit, tins purportedly containing his own feces (although since the work would be destroyed if opened, no i has been able to say for sure). He put the tins on sale for their ain weight in gold. He as well sold his own jiff (enclosed in balloons) as Bodies of Air, and signed people's bodies, thus declaring them to exist living works of art either for all time or for specified periods. (This depended on how much they are prepared to pay). Marcel Broodthaers and Primo Levi are amidst the designated "artworks".

- 1962: Artist Barrie Bates rebrands himself as Billy Apple, erasing his original identity to proceed his exploration of everyday life and commerce as art. By this stage, many of his works are fabricated by tertiary parties.[33]

- 1962: Christo'southward Iron Curtain piece of work. This consists of a battlement of oil barrels in a narrow Paris street which acquired a large traffic jam. The artwork was not the barricade itself but the resulting traffic jam.

- 1962: Yves Klein presents Immaterial Pictorial Sensitivity in diverse ceremonies on the banks of the Seine. He offers to sell his ain "pictorial sensitivity" (whatever that was – he did non ascertain it) in exchange for gilt leaf. In these ceremonies the purchaser gave Klein the gold leaf in render for a certificate. Since Klein'south sensitivity was immaterial, the purchaser was then required to burn the certificate whilst Klein threw one-half the gilt foliage into the Seine. (There were seven purchasers.)

- 1962: Piero Manzoni created The Base of operations of the World, thereby exhibiting the entire planet every bit his artwork.

- 1962: Alberto Greco began his Vivo Dito or Live Art serial, which took identify in Paris, Rome, Madrid, and Piedralaves. In each artwork, Greco called attending to the art in everyday life, thereby asserting that fine art was really a procedure of looking and seeing.

- 1962: FLUXUS Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik in Wiesbaden with George Maciunas, Wolf Vostell, Nam June Paik and others.[34]

- 1963: George Brecht's collection of Effect-Scores, Water Yam, is published as the first Fluxkit by George Maciunas.

- 1963: Festum Fluxorum Fluxus in Düsseldorf with George Maciunas, Wolf Vostell, Joseph Beuys, Dick Higgins, Nam June Paik, Ben Patterson, Emmett Williams and others.

- 1963: Henry Flynt's article Concept Art is published in An Anthology of Chance Operations; a drove of artworks and concepts past artists and musicians that was published by Jackson Mac Low and La Monte Immature (ed.). An Anthology of Chance Operations documented the evolution of Dick Higgins's vision of intermedia art in the context of the ideas of John Cage, and became an early pre-Fluxus masterpiece. Flynt's "concept art" devolved from his idea of "cognitive nihilism" and from his insights about the vulnerabilities of logic and mathematics.

- 1964: Yoko Ono publishes Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings, an example of heuristic art, or a series of instructions for how to obtain an aesthetic experience.

- 1965: Art & Language founder Michael Baldwin's Mirror Piece. Instead of paintings, the work shows a variable number of mirrors that challenge both the visitor and Clement Greenberg'south theory.[35]

- 1965: A circuitous conceptual art piece by John Latham called Still and Chew. He invites fine art students to protest against the values of Clement Greenberg's Fine art and Culture, much praised and taught at Saint Martin's Schoolhouse of Art in London, where Latham taught part-fourth dimension. Pages of Greenberg'southward book (borrowed from the college library) are chewed by the students, dissolved in acid and the resulting solution returned to the library bottled and labelled. Latham was then fired from his part-time position.

- 1965: with Show V, immaterial sculpture the Dutch creative person Marinus Boezem introduced conceptual fine art in the Netherlands. In the show, various air doors are placed where people can walk through them. People take the sensory experience of warmth, air. Three invisible air doors, which arise as currents of cold and warm are blown into the room, are indicated in the infinite with bundles of arrows and lines. The articulation of the space that arises is the result of invisible processes which influence the acquit of persons in that space, and who are included in the system as co-performers.

- Joseph Kosuth dates the concept of One and 3 Chairs to the twelvemonth 1965. The presentation of the work consists of a chair, its photo, and an enlargement of a definition of the word "chair". Kosuth chose the definition from a dictionary. Four versions with different definitions are known.

- 1966: Conceived in 1966 The Air Conditioning Testify of Fine art & Language is published equally an article in 1967 in the November issue of Arts Magazine.[36]

- 1966: N.E. Thing Co. Ltd. (Iain and Ingrid Baxter of Vancouver) exhibit Bagged Place, the contents of a iv-room apartment wrapped in plastic bags. The same yr they registered as a corporation and subsequently organized their practice along corporate models, ane of the first international examples of the "aesthetic of administration".

- 1967: Mel Ramsden's commencement 100% Abstruse Paintings. The painting shows a list of chemical components that constitutes the substance of the painting.[37]

- 1967: Sol LeWitt's Paragraphs on Conceptual Art were published by the American art journal Artforum. The Paragraphs mark the progression from Minimal to Conceptual Fine art.

- 1968: Michael Baldwin, Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge and Harold Hurrell found Fine art & Linguistic communication.[38]

- 1968: Lawrence Weiner relinquishes the physical making of his work and formulates his "Declaration of Intent", one of the most important conceptual art statements following LeWitt's "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art". The declaration, which underscores his subsequent practice, reads: "one. The artist may construct the piece. 2. The slice may exist fabricated. iii. The piece need not be congenital. Each beingness equal and consequent with the intent of the artist the determination every bit to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership."

- Friedrich Heubach launches the magazine Interfunktionen in Cologne, Germany, a publication that excelled in artists' projects. Information technology originally showed a Fluxus influence, but afterward moved toward conceptual art.

- 1969: The kickoff generation of New York alternative exhibition spaces are established, including Billy Apple'due south Apple tree, Robert Newman'due south Gain Ground, where Vito Acconci produced many important early works, and 112 Greene Street.[33] [39]

- 1969: Robert Barry'southward Telepathic Piece at Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, of which he said "During the exhibition I will endeavour to communicate telepathically a work of art, the nature of which is a series of thoughts that are not applicative to language or prototype."

- 1969: The first issue of Art-Language: The Journal of conceptual fine art is published in May, edited by Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Michael Baldwin and Harold Hurrell. Fine art & Language are the editors of this first number, and by the 2d number Joseph Kosuth joins and serves equally American editor until 1972.

- 1969: Vito Acconci creates Following Piece, in which he follows randomly selected members of the public until they disappear into a individual space. The piece is presented equally photographs.

- The English language journal Studio International publishes Joseph Kosuth´s article "Fine art later Philosophy" in iii parts (October–December). Information technology became the virtually discussed article on conceptual art.

- 1970: Ian Burn, Mel Ramsden and Charles Harrison join Art & Language.[38]

- 1970: Painter John Baldessari exhibits a film in which he sets a serial of brainy statements by Sol LeWitt on the subject field of conceptual fine art to pop tunes like "Camptown Races" and "Some Enchanted Evening".

- 1970: Douglas Huebler exhibits a series of photographs taken every ii minutes while driving along a route for 24 minutes.

- 1970: Douglas Huebler asks museum visitors to write down '1 accurate hole-and-corner'. The resulting 1800 documents are compiled into a book which, by some accounts, makes for very repetitive reading as about secrets are similar.

- 1971: Hans Haacke'due south Real Fourth dimension Social System. This piece of systems art detailed the real manor holdings of the third largest landowners in New York Metropolis. The properties, more often than not in Harlem and the Lower East Side, were bedraggled and poorly maintained, and represented the largest concentration of real estate in those areas under the control of a unmarried grouping. The captions gave various fiscal details nearly the buildings, including contempo sales between companies owned or controlled by the aforementioned family. The Guggenheim museum cancelled the exhibition, stating that the overt political implications of the work constituted "an alien substance that had entered the art museum organism". At that place is no evidence to suggest that the trustees of the Guggenheim were linked financially to the family which was the subject of the work.

- 1972: The Art & Linguistic communication Constitute exhibits Index 01 at the Documenta 5, an installation indexing text-works by Fine art & Language and text-works from Art-Linguistic communication.

- 1972: Antonio Caro exhibits in the National Fine art Salon (Museo Nacional, Bogotá, Colombia) his piece of work: Aquinocabeelarte (Art does not fit here), where each of the letters is a split poster, and under each letter is written the name of some victim of country repression.

- 1972: Fred Forest buys an area of blank space in the paper Le Monde and invites readers to make full information technology with their own works of art.

- General Idea launch File mag in Toronto. The magazine functioned equally something of an extended, collaborative artwork.

- 1973: Jacek Tylicki lays out blank canvases or paper sheets in the natural surroundings for nature to create art.

- 1974: Cadillac Ranch near Amarillo, Texas.

- 1975–76: 3 issues of the journal The Play a joke on were published by Art & Language in New York. The editor was Joseph Kosuth. The Fox became an of import platform for the American members of Art & Language. Karl Beveridge, Ian Burn, Sarah Charlesworth, Michael Corris, Joseph Kosuth, Andrew Menard, Mel Ramsden and Terry Smith wrote manufactures which thematized the context of contemporary fine art. These articles exemplify the development of an institutional critique within the inner circle of conceptual art. The criticism of the fine art world integrates social, political and economic reasons.

- 1975–77 Orshi Drozdik's Individual Mythology performance, photography and offsetprint series and her theory of ImageBank in Budapest.

- 1976: facing internal issues, members of Art & Linguistic communication split up. The destiny of the name Art & Language remains in Michael Baldwin, Mel Ramsden and Charles Harrison hands.

- 1977: Walter De Maria'due south Vertical World Kilometer in Kassel, Deutschland. This was a one kilometer brass rod which was sunk into the world then that nil remained visible except a few centimeters. Despite its size, therefore, this work exists mostly in the viewer's mind.

- 1982: The opera Victorine by Fine art & Language was to be performed in the city of Kassel for documenta 7 and shown alongside Fine art & Language Studio at 3 Wesley Place Painted by Actors, merely the operation was cancelled.[40]

- 1986: Art & Language are nominated for the Turner Prize.

- 1989: Christopher Williams' Angola to Vietnam is get-go exhibited. The work consists of a series of black-and-white photographs of glass botanical specimens from the Botanical Museum at Harvard University, called co-ordinate to a list of the 30-six countries in which political disappearances were known to accept taken place during the year 1985.

- 1990: Ashley Bickerton and Ronald Jones included in "Mind Over Affair: Concept and Object" exhibition of "tertiary generation Conceptual artists" at the Whitney Museum of American Art.[41]

- 1991: Ronald Jones exhibits objects and text, art, history and scientific discipline rooted in grim political reality at Metro Pictures Gallery.[42]

- 1991: Charles Saatchi funds Damien Hirst and the adjacent yr in the Saatchi Gallery exhibits his The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a shark in formaldehyde in a vitrine.

- 1992: Maurizio Bolognini starts to "seal" his Programmed Machines: hundreds of computers are programmed and left to run ad infinitum to generate inexhaustible flows of random images which nobody would encounter.[43]

- 1993: Matthieu Laurette established his artistic nascency certificate past taking part in a French Goggle box game called Tournez manège (The Dating Game) where the female person presenter asked him who he was, to which he replied: 'A multimedia creative person'. Laurette had sent out invitations to an art audience to view the show on Idiot box from their homes, turning his staging of the artist into a performed reality.

- 1993: Vanessa Beecroft holds her start operation in Milan, Italy, using models to human activity as a second audition to the display of her diary of food.

- 1999: Tracey Emin is nominated for the Turner Prize. Function of her exhibit is My Bed, her dishevelled bed, surrounded by detritus such as condoms, blood-stained knickers, bottles and her bedroom slippers.

- 2001: Martin Creed wins the Turner Prize for Work No. 227: The lights going on and off, an empty room in which the lights proceed and off.[44]

- 2003: damali ayo exhibits at the Heart of Contemporary Art, Seattle, WA Mankind Tone #1: Skinned, a collaborative cocky-portrait where she asked paint mixers from local hardware stores to create house paint to match various parts of her body, while recording the interactions.[45]

- 2004: Andrea Fraser'due south video Untitled, a certificate of her sexual encounter in a hotel room with a collector (the collector having agreed to help finance the technical costs for enacting and filming the run into) is exhibited at the Friedrich Petzel Gallery. Information technology is accompanied past her 1993 work Don't Postpone Joy, or Collecting Can Exist Fun, a 27-page transcript of an interview with a collector in which the majority of the text has been deleted.

- 2005: Simon Starling wins the Turner Prize for Shedboatshed, a wooden shed which he had turned into a boat, floated downward the Rhine and turned back into a shed again.[46]

- 2005: Maurizio Nannucci creates the large neon installation All Art Has Been Gimmicky on the facade of Altes Museum in Berlin.

- 2014: Olaf Nicolai creates the Memorial for the Victims of Nazi Armed forces Justice on Vienna'south Ballhausplatz afterward winning an international competition. The inscription on top of the iii-step sculpture features a poem by Scottish poet Ian Hamilton Finlay (1924–2006) with just two words: all lonely.

Notable conceptual artists [edit]

- Kevin Abosch (born 1969)

- Vito Acconci (1940–2017)

- Bas January Ader (1942–1975)

- Vikky Alexander (born 1959)

- Francis Alÿs (born 1959)

- Keith Arnatt (1930–2008)

- Art & Language

- Roy Ascott (born 1934)

- Marina Abramović (built-in 1946)

- Billy Apple (born 1935)

- Shusaku Arakawa (1936–2010)

- Christopher D'Arcangelo (1955–1979)

- Michael Asher (1943–2012)

- Mireille Astore (born 1961)

- damali ayo (born 1972)

- Abel Azcona (born 1988)

- John Baldessari (1931–2020)

- Adina Bar-On (born 1951)

- NatHalie Braun Barends

- Artur Barrio (born 1945)

- Robert Barry (born 1936)

- Lothar Baumgarten (1944–2018)

- Joseph Beuys (1921–1986)

- Adolf Bierbrauer (1915–2012)

- Mark Bloch (born 1956)

- Mel Bochner (built-in 1940)

- Marinus Boezem (born 1934)

- Maurizio Bolognini (born 1952)

- Allan Bridge (1945–1995)

- Marcel Broodthaers (1924–1976)

- Chris Brunt (1946–2015)

- María Teresa Burga Ruiz (1935–2021)

- Daniel Buren (born 1938)

- Victor Burgin (built-in 1941)

- Donald Burgy (born 1937)

- Maris Bustamante (born 1949)

- John Cage (1912–1992)

- Cai Guo-Qiang (born 1957)

- Sophie Calle (born 1953)

- Graciela Carnevale (born 1942)

- Roberto Chabet (1937–2013)

- Greg Colson (built-in 1956)

- Martin Creed (born 1968)

- Cory Danziger (born 1977)

- Jack Daws (built-in 1970)

- Jeremy Deller (built-in 1966)

- Agnes Denes (born 1938)

- Jan Dibbets (built-in 1941)

- Mark Divo (built-in 1966)

- Brad Downey (born 1980)

- Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968)

- Olafur Eliasson (born 1967)

- Noemí Escandell (1942–2019)

- Ken Feingold (born 1952)

- Teresita Fernández (built-in 1968)

- Fluxus

- Henry Flynt (born 1940)

- Andrea Fraser (built-in 1965)

- Jens Galschiøt (born 1954)

- Kendell Geers

- Thierry Geoffroy (born 1961)

- Jochen Gerz (born 1940)

- Gilbert and George Gilbert (born 1943) George (born 1942)

- Manav Gupta (born 1967)

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1957–1996)

- Allan Graham (1943–2019)

- Dan Graham (1942-2022)

- Hans Haacke (born 1936)

- Iris Häussler (born 1962)

- Irma Hünerfauth (1907–1998)

- Oliver Herring (born 1964)

- Andreas Heusser (born 1976)

- Jenny Holzer (built-in 1950)

- Greer Honeywill (born 1945)

- Zhang Huan (built-in 1965)

- Douglas Huebler (1924–1997)

- General Idea

- David Republic of ireland (1930–2009)

- Alfredo Jaar (born 1956)

- Ray Johnson (1927–1995)

- Ronald Jones (1952–2019)

- Ilya Kabakov (born 1933)

- On Kawara (1932–2014)

- Jonathon Keats (born 1971)

- Mary Kelly (born 1941)

- Yves Klein (1928–1962)

- John Knight (artist) (born 1945)

- Joseph Kosuth (built-in 1945)

- Barbara Kruger (born 1945)

- Yayoi Kusama (built-in 1929)

- Magali Lara (born 1956)

- John Latham (1921–2006)

- Matthieu Laurette (built-in 1970)

- Sol LeWitt (1928–2007)

- Annette Lemieux (built-in 1957)

- Elliott Linwood (born 1956)

- Noah Lyon (built-in 1979)

- Richard Long (built-in 1945)

- Marker Lombardi (1951–2000)

- George Maciunas (1931–1978)

- Teresa Margolles (born 1963)

- María Evelia Marmolejo (born 1958)

- Piero Manzoni (1933–1963)

- Tom Marioni (born 1937)

- Phyllis Mark (1921–2004)

- Danny Matthys (born 1947)

- Allan McCollum (born 1944)

- Cildo Meireles (born 1948)

- Ana Mendieta (born 1985)

- Marta Minujín (born 1943)

- Linda Montano (built-in 1942)

- Robert Morris (artist) (1931–2018)

- N.E. Affair Co. Ltd. (Iain & Ingrid Baxter) Iain (built-in 1936) Ingrid (built-in 1938)

- Maurizio Nannucci (built-in 1939)

- Bruce Nauman (built-in 1941)

- Olaf Nicolai (born 1962)

- Margaret Noble (born 1972)

- Yoko Ono (born 1933)

- Roman Opałka (1931–2011)

- Dennis Oppenheim (1938–2011)

- Michele Pred

- Adrian Piper (built-in 1948)

- William Pope.50 (built-in 1955)

- Liliana Porter (born 1941)

- Dmitri Prigov (1940–2007)

- Guillem Ramos-Poquí (born 1944)

- Charles Recher (1950–2017)

- Jim Ricks (born 1973)

- Lotty Rosenfeld (1943–2020)

- Martha Rosler (born 1943)

- Allen Ruppersberg (built-in 1944)

- Santiago Sierra (born 1966)

- Bodo Sperling (built-in 1952)

- Stelarc (born 1946)

- M. Vänçi Stirnemann (born 1951)

- Hiroshi Sugimoto (born 1948)

- Stephanie Syjuco (born 1974)

- Hakan Topal (born 1972)

- Endre Tot (built-in 1937)

- David Tremlett (born 1945)

- Tucumán arde (1968)

- Jacek Tylicki (born 1951)

- Mierle Laderman Ukeles (built-in 1939)

- Wolf Vostell (1932–1998)

- Marking Wallinger (born 1959)

- Gillian Wearing (born 1963)

- Peter Weibel (born 1945)

- Lawrence Weiner (born 1942)

- Roger Welch (born 1946)

- Christopher Williams (born 1956)

- xurban commonage

- Manufacture of the Ordinary

- Arne Quinze (born 1971)

See also [edit]

- Post-conceptualism

- Anti-art

- Anti-anti-art

- Body fine art

- Classificatory disputes about art

- Conceptual architecture

- Gimmicky fine art

- Danger music

- Experiments in Art and Applied science

- Found object

- Gutai group

- Happening

- Fluxus

- Information fine art

- Installation art

- Intermedia

- Land fine art

- Modern art

- Moscow Conceptualists

- Neo-conceptual art

- Olfactory art

- Net art

- Postmodern fine art

- Relational art

- Generative Fine art

- Street installation

- Something Else Printing

- Systems art

- Video art

- Visual arts

- Art/MEDIA

Private works [edit]

- Fountain

- One and 3 Chairs

- The Bride Stripped Blank By Her Bachelors, Even

- Mirror Piece

- Secret Painting

- Victorine

References [edit]

- ^ "Wall Drawing 811 – Sol LeWitt". Archived from the original on 2 March 2007.

- ^ Sol LeWitt "Paragraphs on Conceptual Fine art", Artforum, June 1967.

- ^ Godrey, Tony (1988). Conceptual Art (Art & Ideas). London: Phaidon Printing Ltd. ISBN978-0-7148-3388-0.

- ^ Joseph Kosuth, Art After Philosophy (1969). Reprinted in Peter Osborne, Conceptual Fine art: Themes and Movements, Phaidon, London, 2002. p. 232

- ^ Art & Language, Art-Language The Periodical of conceptual art: Introduction (1969). Reprinted in Osborne (2002) p. 230

- ^ Ian Fire, Mel Ramsden: "Notes On Analysis" (1970). Reprinted in Osborne (2003), p. 237. E.one thousand. "The outcome of much of the 'conceptual' piece of work of the by two years has been to carefully clear the air of objects."

- ^ "Turner Prize history: Conceptual art". Tate Gallery. tate.org.uk. Accessed August 8, 2006

- ^ Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Art, London: 1998. p. 28

- ^ "Essay: Concept Fine art". world wide web.henryflynt.org.

- ^ "The Crystallization of Concept Art in 1961". www.henryflynt.org.

- ^ Henry Flynt, "Concept-Art (1962)", Translated and introduced by Nicolas Feuillie, Les presses du réel, Avant-gardes, Dijon.

- ^ "Conceptual Art (Conceptualism) – Artlex". Archived from the original on May 16, 2013.

- ^ Rorimer, p. 11

- ^ Lucy Lippard & John Chandler, "The Dematerialization of Art", Fine art International 12:2, February 1968. Reprinted in Osborne (2002), p. 218

- ^ Rorimer, p. 12

- ^ "Ed Ruscha and Photography". The Art Plant of Chicago. ane March – 1 June 2008. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved xiv September 2010.

- ^ Anne Rorimer, New Art in the Sixties and Seventies, Thames & Hudson, 2001; p. 71

- ^ a b Rorimer, p. 76

- ^ Peter Osborne, Conceptual Art: Themes and movements, Phaidon, London, 2002. p. 28

- ^ Osborne (2002), p. 28

- ^ http://www.fondazioneratti.org/mat/mostre/Gimmicky%20art%20is%20post-conceptual%20art%twenty/Leggi%20il%20testo%20della%20conferenza%20di%20Peter%20Osborne%20in%20PDF.pdf [ dead link ]

- ^ Conceptual Art – "In 1967, Sol LeWitt published Paragraphs on Conceptual Fine art (considered by many to be the movement'due south manifesto) [...]."

- ^ "Conceptual Fine art – The Art Story". theartstory.org. The Art Story Foundation. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Atkins, Robert: Artspeak, 1990, Abbeville Press, ISBN 1-55859-010-two

- ^ Hensher, Philip (2008-02-20). "The loo that shook the globe: Duchamp, Man Ray, Picabi". London: The Independent (Extra). pp. 2–v.

- ^ Judovitz: Unpacking Duchamp, 92–94.

- ^ [1] Marcel Duchamp.net, retrieved Dec 9, 2009

- ^ Marcel Duchamp, Belle haleine – Eau de voilette, Drove Yves Saint Laurent et Pierre Bergé, Christie's Paris, Lot 37. 23 – 25 Feb 2009

- ^ Kostelanetz, Richard (2003). Conversing with John Cage. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93792-2. pp. 69–71, 86, 105, 198, 218, 231.

- ^ Bénédicte Demelas: Des mythes et des réalitées de 50'avant-garde française. Presses universitaires de Rennes, 1988

- ^ Kristine Stiles & Peter Selz, Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists' Writings (Second Edition, Revised and Expanded by Kristine Stiles) University of California Press 2012, p. 333

- ^ ChewingTheSun. "Vorschau – Museum Morsbroich".

- ^ a b Byrt, Anthony. "Brand, new". Frieze Magazine . Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Fluxus at fifty. Stefan Fricke, Alexander Klar, Sarah Maske, Kerber Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-86678-700-ane.

- ^ Tate (2016-04-22), Art & Language – Conceptual Art, Mirrors and Selfies | TateShots , retrieved 2017-07-29

- ^ "Air-conditioning Show / Air Bear witness / Frameworks 1966–67". www.macba.true cat. Archived from the original on 2017-07-29. Retrieved 2017-07-29 .

- ^ "Fine art & Linguistic communication UNCOMPLETED". www.macba.true cat . Retrieved 2017-07-29 .

- ^ a b "BBC – Coventry and Warwickshire Civilization – Fine art and Language". www.bbc.co.united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland . Retrieved 2017-07-29 .

- ^ Terroni, Christelle (7 October 2011). "The Rise and Fall of Alternative Spaces". Books&ideas.net . Retrieved 28 Nov 2012.

- ^ Harrison, Charles (2001). Conceptual art and painting Farther essays on Fine art & Linguistic communication. Cambridge: The MIT Printing. p. 58. ISBN0-262-58240-6.

- ^ Brenson, Michael (xix October 1990). "Review/Art; In the Arena of the Mind, at the Whitney". The New York Times.

- ^ Smith, Roberta. "Fine art in review: Ronald Jones Metro Pictures", The New York Times, 27 December 1991. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ Sandra Solimano, ed. (2005). Maurizio Bolognini. Programmed Machines 1990–2005. Genoa: Villa Croce Museum of Contemporary Art, Neos. ISBN88-87262-47-0.

- ^ "BBC News – ARTS – Creed lights up Turner prize". x December 2001.

- ^ "Third Coast Sound Festival Behind the Scenes with damali ayo".

- ^ "The Times & The Sunday Times". world wide web.thetimes.co.britain.

Further reading [edit]

- Books

- Charles Harrison, Essays on Fine art & Language, MIT Printing, 1991

- Charles Harrison, Conceptual Art and Painting: Farther essays on Fine art & Language, MIT press, 2001

- Ermanno Migliorini, Conceptual Fine art, Florence: 1971

- Klaus Honnef, Concept Fine art, Cologne: Phaidon, 1972

- Ursula Meyer, ed., Conceptual Fine art, New York: Dutton, 1972

- Lucy R. Lippard, 6 Years: the Dematerialization of the Art Object From 1966 to 1972. 1973. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

- Gregory Battcock, ed., Idea Art: A Critical Album, New York: E. P. Dutton, 1973

- Jürgen Schilling, Aktionskunst. Identität von Kunst und Leben? Verlag C.J. Bucher, 1978, ISBN 3-7658-0266-2.

- Juan Vicente Aliaga & José Miguel G. Cortés, ed., Arte Conceptual Revisado/Conceptual Fine art Revisited, Valencia: Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, 1990

- Thomas Dreher, Konzeptuelle Kunst in Amerika und England zwischen 1963 und 1976 (Thesis Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München), Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1992

- Robert C. Morgan, Conceptual Fine art: An American Perspective, Jefferson, NC/London: McFarland, 1994

- Robert C. Morgan, Art into Ideas: Essays on Conceptual Fine art, Cambridge et al.: Cambridge Academy Press, 1996

- Charles Harrison and Paul Forest, Art in Theory: 1900–1990, Blackwell Publishing, 1993

- Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Fine art, London: 1998

- Alexander Alberro & Blake Stimson, ed., Conceptual Art: A Disquisitional Album, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: MIT Press, 1999

- Michael Newman & Jon Bird, ed., Rewriting Conceptual Art, London: Reaktion, 1999

- Anne Rorimer, New Art in the 60s and 70s: Redefining Reality, London: Thames & Hudson, 2001

- Peter Osborne, Conceptual Art (Themes and Movements), Phaidon, 2002 (Run into also the external links for Robert Smithson)

- Alexander Alberro. Conceptual art and the politics of publicity. MIT Press, 2003.

- Michael Corris, ed., Conceptual Art: Theory, Practice, Myth, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2004

- Daniel Marzona, Conceptual Fine art, Cologne: Taschen, 2005

- John Roberts, The Intangibilities of Course: Skill and Deskilling in Art After the Readymade, London and New York: Verso Books, 2007

- Peter Goldie and Elisabeth Schellekens, Who's afraid of conceptual art?, Abingdon [etc.] : Routledge, 2010. – 8, 152 p. : sick. ; 20 cm ISBN 0-415-42281-7 hbk : ISBN 978-0-415-42281-9 hbk : ISBN 0-415-42282-v pbk : ISBN 978-0-415-42282-half dozen pbk

- Essays

- Andrea Sauchelli, 'The Acquaintance Principle, Aesthetic Judgments, and Conceptual Art, Journal of Aesthetic Education (forthcoming, 2016).

- Exhibition catalogues

- Diagram-boxes and Analogue Structures, exh.true cat. London: Molton Gallery, 1963.

- Jan v–31, 1969, exh.true cat., New York: Seth Siegelaub, 1969

- When Attitudes Become Form, exh.cat., Bern: Kunsthalle Bern, 1969

- 557,087, exh.cat., Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1969

- Konzeption/Conception, exh.true cat., Leverkusen: Städt. Museum Leverkusen et al., 1969

- Conceptual Art and Conceptual Aspects, exh.true cat., New York: New York Cultural Middle, 1970

- Fine art in the Listen, exh.cat., Oberlin, Ohio: Allen Memorial Art Museum, 1970

- Information, exh.cat., New York: Museum of Modern Fine art, 1970

- Software, exh.cat., New York: Jewish Museum, 1970

- State of affairs Concepts, exh.cat., Innsbruck: Forum für aktuelle Kunst, 1971

- Art conceptuel I, exh.true cat., Bordeaux: capcMusée d'art contemporain de Bordeaux, 1988

- L'art conceptuel, exh.cat., Paris: ARC–Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1989

- Christian Schlatter, ed., Art Conceptuel Formes Conceptuelles/Conceptual Art Conceptual Forms, exh.true cat., Paris: Galerie 1900–2000 and Galerie de Poche, 1990

- Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965–1975, exh.true cat., Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1995

- Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s, exh.cat., New York: Queens Museum of Fine art, 1999

- Open up Systems: Rethinking Fine art c. 1970, exh.cat., London: Tate Modern, 2005

- Art & Language Uncompleted: The Philippe Méaille Collection, MACBA Press, 2014

- Light Years: Conceptual Art and the Photo 1964–1977, exh.cat., Chicago: Art Constitute of Chicago, 2011

External links [edit]

robinsondifes2000.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conceptual_art

0 Response to "Art Installation of Life Size Plastic Alien Guy Not Fitting in"

Post a Comment